Iron, brass and nickle or white

brass were used for locks, handles, hinges, decorations and structural braces. Cut-out and

etched brass fittings and locks were superbly designed and crafted for each chest or box.

Locks were things of beauty quite apart from their utilitarian purpose. Silver locks

inlaid with gold, black iron inlaid with silver, brass carved into the shapes of

propitious animals and fish, and octagonal locks with the characters for prosperity and

long life were made in various sizes. Most locks are of a padlock design to hold together

two links or rings affixed to doors.

Iron decorations were used in kitchen pieces, for it was obvious that brass tarnished

quickly from the carbon monoxide of the cooking fire.

|

|

We think of the wardrobe as a place to hang our clothes. But it

would be more accurate to speak of Korea's traditional wardrobe as

a place to pile clothes. ln

Korea's wardrobe the clothes are folded and stacked on top of each

other. That is why, when we look inside, we sometimes feel we are

looking down into the depths of a well. Indeed, when we step back

and observe those clothes piled on top of each other, we are

reminded of the earth's geological strata. We might equate the

deepest layer, way at the bottom, with the earth's core, and the

top of the stack with the earth's surface.

|

|

| Each layer

has its own special nature. In the summer, the layer way down at the

bottom is winter clothing, but after a few months has passed, look again

-now the summer clothing is buried down there. And the layers in the

middle will hold clothing for the more temperate months. So the strata

revolve according to the revolution of the seasons.

It is not only seasonal change that determines

what is on the floor of the wardrobe. The very difficulty involved in

pulling something out from way down inside there affords a place to secure

the family's valuables. Embedded in the deepest fathoms of the wardrobe we

will find the anchor which stabilizes and secures the family through the

storms that life will now and then send its way.

That is why, though the Korean wardrobe is not all

that high, its depth is an abyss. One cannot locate the valuables stored

in the wardrobe simply by opening it up and looking inside. The clothing

covering these valuables has to be taken out, piece by piece. The Korean

wife or mother looking for some valuable can resemble some prospector

digging away shovel by shovel, or the pearl diver pushing down, down and

around among the coral reefs. Whether it be a worn out piece of clothing

or some yellowing family photo, each item uncovered during the search

receives a special greeting in the mother's smile, or in her sigh. This

welcome can sometimes come close to the exclamations an archeologist will

utter in the process of excavating an ancient tomb. In the depths of the

wardrobe are things lost to time, forgotten in life's forced march,

naturally receiving a special welcome when they surface again and beckon

us to stay a bit and remember.

This stratified structure is inherent in every

Korean chest no matter what kind or size of chest it is. It does not have

to be a fullsized wardrobe. It may be the chest for boot socks, which

looks like a child's miniature of the larger wardrobe, but has that same

indeterminable depth. Whether it is a chest divided into several

compartments, like the wardrobe, or of just one cavity with nothing more

than its floor to serve as its one and only "shelf," any Korean

chest has its layers and its bottomless bottom.

The wardrobe does not come in only one size or

type. The feature which best distinguishes one wardrobe from another is

the number of levels it has, and we name them accordingly. There is the

two-shelf wardrobe, the three-shelf wardrobe, and so on. As the eye

follows these shelves up or down, as it alights on each of the shelves and

on the layers of clothing stacked on them, one begins to sense a regular

rhythm there. Then again, in each wood shelf nature provides an irregular

pattern in the grain of the persimmon tree or the paulownia. We can see in

this regular rhythm and irregular pattern the beauty of a mosaic, and this

mosaic is enhanced by the varied patterns and colors of the clothes

stacked several high on each shelf.

The Korean wardrobe is a composition of a simple

rhythm weaving colors and textures into a mosaic of life. Though its

contents are not locked up as if in a safe, they are protected from prying

hands by the wardrobe's ever revolving depths. Never locked, in its

fathomless depths it nevertheless safeguards its most precious things, as

does the heart of the Korean mother.

|

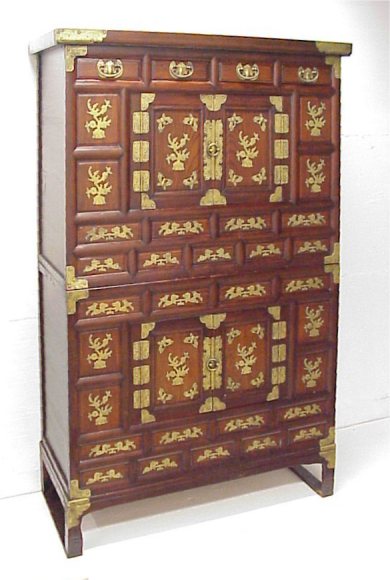

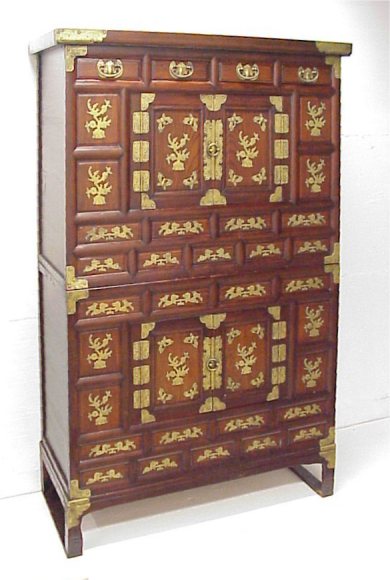

The design of furniture was

dictated in part by the designs and styles prevalent in the place of construction, the

regional climates, and by the traditional shapes and decorations associated with usage. As

people began to travel, some geographically dictated distinctions began to blur. But

origin is usually identifiable by the wood work and the differences in ornamentation.

Cholla-do was a rich farming

area. Here various woods were found and the furniture were of excellent quality. Persimmon

was frequently used for the furniture of wealthy land owning farmers.

Kyungsang-do also produces furniture of many woods and brass ornaments of superb quality

as this province too was the home of yangban families.

Chungchung-do was the seat of many aristocratic families. Dignified furniture, often made

of paulownia, was produced in this area.

Kangwon-do furniture are of many stylers reflecting the influences of the other provinces. It was here that officials

took refuge when dismissed from government service. Many brought their household

possessions which local craftsmen would copy.

The Kyunggi area surrounds the capital, Hanyang, where furniture were made for the great

palaces, for the court and the important official families attached to it. But many

furniture are of pine, few other wood being readily available.

|

Ganghwa

island Dolmens |

Ganghwa island, where royalty fled

from Seoul to escape foreign invasions, also produces exquisite

furniture pieces elaborately covered with brass ornaments.

The greater area of Ganghwa consisting of 29

islands in the Yellow Sea. Farming, especially ginseng and rice as well

as fishing are important. The largest island was briefly the site of the

Korean capital in the 13th cent. It was early fortified as an outer

defence for Seoul and was stormed and occupied by the French in 1866 and

by the Americans in 1871.

|

Farther north, in what is now North Korea, little wood other than pine covered the hills.

The craftsmen used whatever was available, covering most of the surface of the furniture

with metal ornaments. |