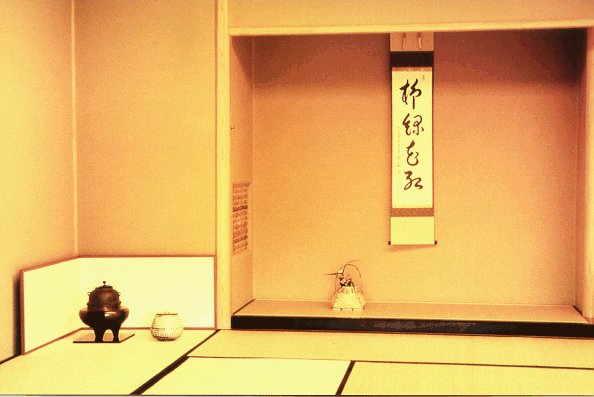

Tatami, Japan's traditional flooring

|

Tatami refers to a

type of flooring common to the traditional Japanese home. When

the people of ancient Japan lived in primitive dwellings with

earthen floors, the custom of covering floors with straw, husks,

or other plant fibers developed. Later, these fibers were woven

together to form a mat, called tatami. These first forms of

tatami were used exclusively by the privileged classes - the

nobility, the clergy, and the samurai - and assumed the

functions of chair, cushion, bed, and stool. In the 15th century, samurai began completely covering floors with tatami; it would take another three centuries for this custom to be adopted by the common person. |

|

The making of tatami

is intricate and requires years of study. The first step is the

making of the main body, or toko, from wara - the stalks of rice

plants after the rice has been harvested. The rice stalks are

placed in a stack measuring approximately thirty centimeters and

compressed to about one-fifth the thickness. Today, tatami artisans are having to import rice stalks from Korea, China, and Taiwan, since an adequate supply cannot be had in Japan. |

For the second step, a thin mat made from the woven stems of rush plants,

chosen for their fresh smell and greenery, is stretched tightly over and

sewn to the toko to create the tatami facing. Finally, the tatami

artisan attaches the heri to the length of the tatami. The heri is a

piece of cloth sewn along the sides to prevent the tatami from

unraveling While a highly skilled tatami artisan can complete the second

and final step in one hour, modern machinery can finish these two steps

in about ten minutes.

The tatami artisan visits the home to determine the size and number of

tatami needed for a room - the tatami must fit the floor of the room

perfectly and snugly, like the pieces of a jigsaw puzzle. The tatami

artisan sets the completed tatami mats into the floor, with only the

facings visible. Because the green stems of the rush plants turn a straw

yellow with time, in the past, it was common for the tatami artisan to

again visit the home a year later to turn over the facing so that the

under side of the mat would face up. Another year would go by, after

which, the tatami facing would be completely replaced with a fresh set.

This custom is rarely practiced - and even unknown - today, as many

young Japanese have begun covering tatami with carpeting to create a

Western look.

Over the years, tatami have been ranked according to the quality of the

materials and the craftsmanship. However, increased urbanization, and

the demand for reasonably-priced housing, have stimulated the need for

lower cost tatami. Cheaper materials such as Styro-foam have been

substituted in the toko; heri made from synthetic fibers have also

become quite common.

A second effect of urbanization has been on the size of tatami. Usually,

the tatami's length is two times the width, about 180 by 90 cm. In

Japan, since room sizes are often compared by the number of tatami it

takes to cover the floor - for example, a six-mat room - people have a

general image of how big a six-mat room should be. However, the high

concentration of people in the cities has resulted in smaller housing

units. Tatami sizes were reduced to between 70 and 80 cm. in width, in

order to maintain the illusion of standard room size. These smaller

tatami are referred to as danchi-size and are quite common in modern

housing. Young Japanese feel this reduction keenly, since their average

height has considerably increased over the years.

Tatami have a long history and are closely identified with Japanese

culture. However, like many traditions they have had to struggle against

the tide of modern progress: The number of tatami artisans has declined,

while western-style flooring has grown in popularity; because most

tatami are made by machines, few are trained in traditional handmade

tatami making. In spite of this, tatami are enjoying greater popularity

both at home and abroad (Asian countries, in particular). Deep down,

Japanese know - what others are just finding out - there is no

substitute for the fresh smell of tatami or the unique atmosphere these

mats create.